The Dunkin’ Beanpot Tradition

The Dunkin’ Beanpot, Boston's "social event of the winter season," has been a beloved tradition since its debut on December 26, 1952, at the old Boston Arena. Featuring Boston College, Boston University, Harvard, and Northeastern, this annual hockey tournament moved to the Garden the following year, where it has remained, becoming the ultimate battle for Boston's hockey bragging rights. Over the decades, the Beanpot has grown in stature and popularity, creating unforgettable memories for players, coaches, fans, and media alike. In 2001, it celebrated its 50th edition, a milestone captured in a commemorative piece by Hockey East Commissioner and former participant Joe Bertagna.

The Beanpot At 50 - By Joe Bertagna

Despite being confined to a Veterans Administration hospital in the final years of his life, Bill Hutchinson would clack out an annual request for Beanpot tickets on an old manual typewriter each January. Bill was an old friend, a former referee who later in life served the Eastern College Athletic Conference (ECAC) as Supervisor of Officials. I knew he couldn't use the tickets himself but I never asked any questions. I just got him four for each night.

About a year before he died, the ticket request came with an unsolicited explanation.

"You have probably been wondering all these years what I do with these tickets," the note said. "I get them each year for the doctors here at the V.A. Hospital. And I swear to God that the only reason they keep me alive is for these damn tickets."

The Beanpot may not be a life or death matter for most of us. But it is a big deal and has been a big deal for most of its half century of inspiring athletes and entertaining fans. It is a half century that has seen great changes in the world, in amateur athletics, and in college hockey itself. But for all the changes, the competition for the 'Pot has remained relatively unaffected by all that has evolved around it.

It is difficult to remember, given the success it has become, what the Beanpot's original intent was.

"It was designed as a filler," says Northeastern's Jack Grinold, the unofficial historian of all things Beanpot. "I mean, it was originally the first two nights after Christmas of 1952. It was to help the Arena on off nights. It's way, way beyond that now."

The early history is somewhat familiar to most Beanpot fans. The games were played in the Boston (now Matthews) Arena for one year (1952), before moving to the Boston Garden. The games were played on consecutive nights for the first three years and then within a few days for a couple of years. The first games were played in December of 1952 and January of 1954, leaving Calendar Year 1953 without a Beanpot.

It wasn't until the sixth year that the current "first two Mondays in February" format was adopted and it wasn't until the ninth year, 1961, that the magic number of 13,909 provided the event's first sellout. It has been the hottest of tickets ever since.

The White House has seen ten Presidents since Beanpot I, and Fenway Park has been home to even more Red Sox managers in that time. You couldn't check in the offensive zone back then. No one wore facemasks. Not even the goalies.

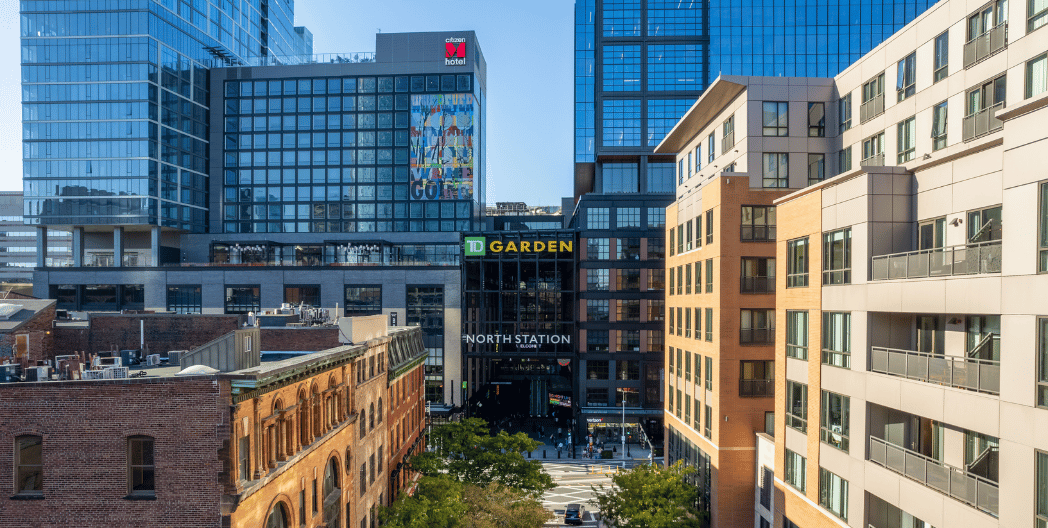

The Garden is no longer with us. Gone are those thundering crowds. And the bad ice. But not the memories. The FleetCenter now houses the event and is in the process of creating new memories. Where Harvard's Bill Cleary might say, "Hey, it was a thrill to play where Milt Schmidt played," and former B.U. star (now Bowdoin head coach) Terry Meagher might say, "It was thrilling to play where Orr played," today's undergraduates are likely "thrilled" to play where Ray Bourque played.

Boston College coach Jerry York remembers taking public transportation to the Beanpot, as a freshman, who along with all other freshmen, couldn't play in the Beanpot. And he remembers taking that same public transportation, gear in hand, for three years when he did play. "The schools didn't take team buses in those days," he recalls.

Terry Meagher remembers being confused by all the attention given the tournament. "I remember thinking, 'Hey, these are ECAC games. We need these for the league title first.' But then I remember how the Beanpot made Boston feel smaller, like a more sociable place to someone like me from Canada. Everyone seemed interested in college hockey when the Beanpot drew near."

The games were all "league games" when there was just one league, the ECAC. Opening games, consolation games, championship games ÷ they all counted in the ECAC standings, in those days before common schedules and split allegiances (ECAC vs. Hockey East).

Along with formats and buildings and leagues, the hockey culture has changed. It has become, for better and worse, professionalized. Kids leave their local youth program for more competitive opportunities. They leave their local high schools for private schools or prep schools or both. They leave home for junior teams in the Midwest or for an elite program run by USA Hockey. They have personal trainers. They expect to play professional hockey. And some, a handful, do.

What hasn't changed about the Beanpot is when it is and what it is. And don't kid yourself: the "when" is no small part of the phenomenon. Early February brings cabin fever to New England and the region's sports fans are excited by even the mention of pitchers and catchers reporting to Florida. Where else can print and broadcast images of a generic rental van loaded with baseball gear bring grown men to tears? It is at this moment that the area needs a boost, something special to get excited about. And the Beanpot provides a diversion.

That the games are played on Monday evenings, Jack Parker has observed, further elevates the Beanpot. "There are relatively few events competing with the Beanpot," notes Parker. "So the media discover us each year and ask us, 'Hey, why is this so big?' And I look at the guy and say, 'Because you're here.'"

College hockey devotees are used to working a little harder to follow their sport. You want to know who won the Duke-Maryland basketball game? Look anywhere. Local paper. Televison. Radio. You'll find it. You're trying to find out who won the Minnesota-St. Cloud game that will determine who is #1 in college hockey this week? Saint who? Go on-line.

Ah, but then February. Sports editors, who allowed us a pre-season preview in October and plan to cover our tournaments in March, throw us a bone. They cover the Beanpot. Hey, it sells out the FleetCenter, it's a good story line, and, well, it's a Monday night in February. And this leads to a question: does the spotlight aimed at the Beanpot elevate the play or does the quality of the play provide that greater spotlight? Perhaps it's a little of both.

Of course, to relegate this event to a freak of scheduling is to miss the point. And so we come to "what" it is.

"The fact that it's the same four schools makes all the difference in the world," says BU's Parker.

Bill Cleary takes it a step further. "It's not just that the same schools are there but that they are so close to each other. The Great Lakes Invitational has three of the same schools each year but how far apart are Michigan and Michigan Tech and Michigan State? This is the most unique tournament of its kind and it's what amateur athletics is all about."

It hasn't hurt that those four schools play the game pretty well. Three of them have won national championships in the last 13 years, which means you are watching, more often than not, some of the best college hockey in the country. And that makes it a damn hard event to win.

"It has become an aside to the real season," observes Parker. "Almost a preposterous aside. It shouldn't mean as much as it does."

Parker's Terriers have enjoyed a preposterous record of success in this tournament (appearances in 18 of the last 20 finals, for example), one that has sometimes dulled the pleasure of the Beanpot for non-Terriers. Playing with talent and without the pressure of "needing" to win it, the Terriers have won six of the last seven. How tough is it to win?

"In the 1980's, we went to the NCAA Frozen Four four times, the final game three times, and won it once," says Bill Cleary. "In that same period, we only played in two Beanpot finals and, fortunately, won them both."

It has not been by accident that the games have retained their appeal. The schools and the host building, under the watchful eye of Steve Nazro, have protected what is special about the Beanpot.

"We have always tried to keep the focus on the players and the coaches," says Nazro. "We rotate who plays whom, there are no "seeds", for example. And while the tournament has been successful financially, we've never made the bottom line our first priority."

In other words, Nazro, and the likes of Cleary, Grinold, and the late Bill Flynn, for example, have insured that we aren't attending the "Something.Com Beanpot" tonight. The event's stewards have protected the Beanpot's special traditions yet have spurred growth through television coverage, a Beanpot Hall of Fame, and a series of special projects surrounding this 50th birthday.

Television has allowed the average fan to watch the action at home while the Beanpot ticket becomes more difficult to find each year. As NU's Grinold observes, "I get a kick out of its sustaining power. It's growing by the year."

With the alumni base of the four schools growing each year, and the cost of tickets to professional games going through the roof, the Beanpot looks more attractive by contrast. College hockey in general has enjoyed a growth in recent years, judging from record crowds at conference and NCAA championships.

Some, this writer included, have lamented the growing number of "suits" in the building each year, "fans" who attend but one (two?) college hockey games a year. Others guarantee their Beanpot tickets by purchasing season tickets at one of the four campus rinks, a strategy out of reach for many families with youth hockey-aged children. And so NESN becomes the link for future Beanpot stars.

Speaking of future stars, it is not surprising that the Beanpot has become a major recruiting tool for the four schools. Television enhances that capability. And this makes it ironic that Bob Norton has become so familiar as one of the Beanpot's voices.

"I never went to a Beanpot when I coached," said the former UNH assistant recently. "I couldn't afford to be seen there. And when you talked to a recruit, you never mentioned the Beanpot. It was as if it didn't exist." Norton, a Watertown native who now serves as the principal of Woburn High School, has since broadcast eight or nine Beanpots with the enthusiasm of a true Bostonian.

Jerry York, another Watertown native, recalls his days at Bowling Green, between his old Beanpot playing days and current Beanpot coaching stint.

"My assistant was Buddy Powers, who grew up in Hyde Park and played in the Beanpot for BU," recalls York. "We used to find a bar that had the games on the satellite and we'd watch the games and argue back and forth."

While the games are primarily for the players and coaches, the alumni aren't far behind. That the same local schools make up the field allows for stories like York's to flow from former players to non-playing alumni alike.

Stories have long been part of the Beanpot experience. We've all heard about Bill Cleary's famous goal and Snooks Kelley's telling of it. Everyone has a Blizzard of '78 story. On just about everyone's Top Ten List is Wayne Turner's goal that gave Northeastern it's first Pot.

And from the stories, we discover what the Beanpot is about then as well as now. It is about games and memories and basic emotions. If you played in it and never won it, it gnaws at you when you come back to watch. I know. Others who have won it, when discussing a great player from another era, might suddenly limit their assessment of the individual with a terse, "But he never won a Beanpot."

Jack Parker, who proudly recalls being 27-1 against Beanpot schools during his three years as a Terrier, remembers fondly his first Beanpot as a coach back in 1975.

"Harvard shellacked us pretty good in December, 7-2, and we got another shot at them in the Beanpot," he recalls. "We beat them by the same score. And I knew we were going to win that game. Both teams had only one or two losses. But I knew we would win that game."

The record books show that Bill Cleary holds the Beanpot records for goals in a period (4), game (5), and tournament (7). There are teams that didn't score five goals in two games. The record book doesn't show who has taken part in the most Beanpots but few can match Cleary's personal history. He played in two, officiated in six or seven (he can't be sure), coached in 22, and was athletic director for ten. His special memories have nothing to do with his own performances.

"I'll never forget the year I called up a kid named Lyman Bullard (now an owner of the AHL's Portland Pirates)," recalls Cleary. "He was a great athlete who played varsity soccer and tennis but had only played JV hockey for us. I don't even think he ever tried out for the varsity but just came out for JVs after soccer.

"He roomed with Brian Petrovek (also with Portland now) and I can still remember calling the room and Lyman answering the phone. He's all excited, saying, 'We're going to be in there rooting for you tomorrow night, Coach.' And I just said, 'How'd you like to play?'

"Well, he is so excited and don't you know he goes out and scores a goal and we win the thing. And he never plays another varsity game."

Then Cleary recalls a moment to which many of us can relate. As he was wont to do, Cleary invited the little brother of one of his players to be on the bench during the Beanpot as a stickboy. The nine-year old is visiting from Ontario just for the tournament. He has seen the Boston Garden on televsion during "Hockey Night In Canada" broadcasts. And now he is there.

"We were getting hammered by Boston University in the first period and finally it ends," says Cleary. And we have to walk across the ice to our dressing room, the little kid and my own son, who was also nine at the time, leading the way.

"Then suddenly, as we get to the big 'B' at center ice, the little guy just drops down as if he is taking a face-off. He's in the middle of 14,000 people, we're getting killed by BU and he is completely oblivious to it all. He saw that 'B' like he had so many times on television. And now it was his turn to take the draw."

Tonight, somewhere in the suburbs, or here in the FleetCenter, there is a little kid thinking about taking the draw or scoring the winning goal or, allow me, making the big save. In his dream, he is wearing the colors of his favorite Beanpot team. And some day, in five years or ten, you may very well be watching a young boy's dream come true.

And that is one more thing about the Beanpot that has not changed in 50 years.

Joe Bertagna played goal for Harvard in the 1972 and 1973 Beanpot tournaments. A frequent contributor to the Beanpot programs over the years, Bertagna serves college hockey today as Executive Director of the American Hockey Coaches Association and as Commissioner of Hockey East.

No Beanpot? - A poem by Bill Littlefield

They tell me there was once no Beanpot, but I can't be sure,

Because without the Beanpot, how could anyone endure

The black ice and the bitter cold, and all the dirty snow

That's February's dreary portion everywhere you go?

This month that's coming up without the tourney? I think not.

In February, here in Boston, this is what you've got.

From Huntington to Commonwealth, across to Harvard Square,

The wind will freeze your tail off, and you'll wish that you weren't there...

Except you've got the Beanpot on two cold, dark Monday nights,

And that's the thought that warms the heart and turns on all the lights,

And calls forth all the memories of Beanpot yore...

Like '68, when Harvard got just one, and B.U. four.

Or how about a recent year more mem'rable to me?

In '01 B.C. banged home five, and B.U. only three.

And if you drop a decade back, and I'm prepared to do,

You find in '93 that Harvard, strange, I know, but true,

Let B.U. slip a couple in, but scarcely any more,

Which worked out for the Crimson, as they neatly netted four.

And thirteen years before that night, the stars swirled into line,

And as those gathered gaped and gasped, Northeastern bowed the twine

Not once, not twice, but full five times, which B.C. couldn't do,

And in overtime which was completely overdue,

Northeastern won the Pot, and Jack Grinold, a happy guy,

Became convinced that heaven had descended from the sky.

Two Monday evenings loom before us, glorious and grand —

These nights of hockey, nights of chanting, nights of bleating bands

Have now for half a century been February's lot,

And, as I've said, in winter, it's the best that Boston's got.

Good luck to the competitors, to all the rest good cheer.

Whoever wins, may you all gather for the Pot next year.

Bill Littlefield is a noted author and the host of NPR's popular "Only a Game" program. He graduated from Yale and then earned a graduate degree at Harvard.

What the Beanpot means to me? Quite simply, there are two words that come to mind: tradition and emotion. Anyone who has a pulse around here knows about the tradition of the Beanpot. I'm a local kid. I grew up in Scituate. I started coming to the Beanpot about the same time I started playing hockey.

David Silk, Former BU forward and 1980 Olympic gold medal winner

Latest News

View All-

Posted Mar 28, 2025

TD Garden Nominated for ‘Arena of The Year’ by the Academy of Country Music

-

Posted Mar 17, 2025

TD Garden Named Finalist for 2025 SBJ Sports Business Awards' Facility of the Year

TD Garden is thrilled to announce its nomination as a finalist for the prestigious Sports Business Journal's 2025 Sports Business Awards' Facility of the Year.

twitter

Follow